Pinellas Park, Florida

Pinellas Park | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Simply Centered" | |

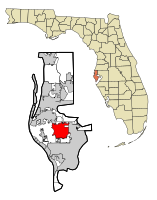

Location in Pinellas County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 27°51′8″N 82°42′26″W / 27.85222°N 82.70722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Pinellas |

| Settled | 1911 |

| Incorporated | October 14, 1914 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Sandra Bradbury (R) |

| • Vice Mayor | Patti Reed |

| • Councilmembers | Tim Caddell, Ricky Butler, and Keith V. Sabiel |

| • City Manager | Bart Diebold |

| • City Clerk | Jennifer Carfagno |

| Area | |

• Total | 16.80 sq mi (43.51 km2) |

| • Land | 16.13 sq mi (41.76 km2) |

| • Water | 0.68 sq mi (1.75 km2) |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 53,093 |

• Estimate (2023)[2] | 53,456 |

| • Density | 3,292.59/sq mi (1,271.27/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 33780–33782 |

| Area code | 727 |

| FIPS code | 12-56975[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0288936[4] |

| Website | www |

Pinellas Park is a city located in central Pinellas County, United States. The population was 53,093 at the 2020 census.[5] The city is the fourth largest city in Pinellas County. The City of Pinellas Park was incorporated in 1914. It is part of the Tampa–St. Petersburg–Clearwater Metropolitan Statistical Area, most commonly referred to as the Tampa Bay Area.

History

[edit]The city was founded by Philadelphia publisher F. A. Davis, who purchased 12,800 acres (52 km2) of Hamilton Disston's land around 1911.[6] Davies used promotional brochures to lure northerners, especially Pennsylvanians, to the town, noting the pleasant climate in the winter and the agreeable agricultural conditions. The Florida Association, a corporation, set up model farms and offered a free lot in the city with the purchase of ten acres of nearby farm land. A two-story building called the Colony House was established to house prospective purchasers of the available farm plots.[7] The primary crop that the founders intended to grow on the farms they established was sugar cane. By 1912, lots in the city were being sold separately.[8] The City of Pinellas Park was formally incorporated on October 14, 1914.[9][10]

Though not on the original Orange Belt Railway, Pinellas Park did have a train depot, razed in 1970, on the line between Clearwater and St. Petersburg. The city lay on the vehicle road from St. Petersburg to Tampa. Growth was moderate until after World War II, when the city's population more than tripled.[11]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 16.2 square miles (41.9 km2), of which 15.5 square miles (40.2 km2) is land and 0.66 square miles (1.7 km2) (4.14%) is water.[12]

Pinellas Park city limits are contiguous with those of St. Petersburg, Clearwater, Largo, Seminole, Kenneth City, and unincorporated areas of Pinellas County. Annexation into the city is voluntary by both the property owner and the City Council.

Because of the city's relatively low elevation between major bodies of water, and its generally flat topography, it has historically been subject to flooding. Through construction of a network of drainage canals and other measures by the Pinellas Park Water Management District, flooding in the city has been greatly mitigated.[13]

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild winters. According to the Köppen climate classification, the City of Pinellas Park has a humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa).

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 134 | — | |

| 1930 | 465 | 247.0% | |

| 1940 | 691 | 48.6% | |

| 1950 | 2,924 | 323.2% | |

| 1960 | 10,848 | 271.0% | |

| 1970 | 22,287 | 105.4% | |

| 1980 | 32,811 | 47.2% | |

| 1990 | 43,426 | 32.4% | |

| 2000 | 45,658 | 5.1% | |

| 2010 | 49,079 | 7.5% | |

| 2020 | 53,093 | 8.2% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 53,456 | 0.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

2010 and 2020 census

[edit]| Race | Pop 2010[15] | Pop 2020[16] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 36,851 | 34,025 | 75.09% | 64.09% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 2,133 | 3,464 | 4.35% | 6.52% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 119 | 119 | 0.24% | 0.22% |

| Asian (NH) | 3,535 | 5,171 | 7.20% | 9.74% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 55 | 47 | 0.11% | 0.09% |

| Some other race (NH) | 131 | 357 | 0.27% | 0.67% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 989 | 2,560 | 2.02% | 4.82% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 5,266 | 7,350 | 10.73% | 13.84% |

| Total | 49,079 | 53,093 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 53,093 people, 20,746 households, and 12,344 families residing in the city.[17]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 49,079 people, 20,565 households, and 12,553 families residing in the city.[18]

2000 census

[edit]Linguistically in 2000, 76.1% of the population over the age of five reported speaking only English at home, while 23.9% reported speaking some other language.

As of 2000, there were 20,746 households, out of which 22.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.8% were married couples living together, 10.2% had a female householder with no spouse present, 6.6% had a male householder with no spouse present, and 40.4% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.22.

In 2000, in the city, the population was spread out, with 20.3% under the age of 20, 10.4% from 20 to 29, 14.3% from 30 to 39, 12.5% from 440 to 49, 20.5% from 50 to 64, and 22.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43.6 years. 47.1% of the inhabitants were male and 52.9% were female. Like many areas in Florida, the population of Pinellas Park swells temporarily, but substantially, for half the year as mostly-retired adults (called "snow birds"), who reside elsewhere in the northern states or Canada during the summer, come to Florida for its mild winter climate.

As of 2000, educational statues surveys showed that among those 25 and older 14.3% did not have a high school diploma, while 32.4% had only a high school diploma, 19.8% had some college experience without a degree, 25.8% had an Associate's or bachelor's degree, and 7.7% had a graduate or professional degree.

In 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $58,526, and the median income for a family was $58,526. Males had a median income of $44,616 versus $38,510 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,701. About 9.0% of families and 13.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.8% of those under age 18 and 11.2% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and Culture

[edit]Fine arts

[edit]The Pinellas Park Civic Orchestra and the Sunsation Show Chorus perform regularly in the City-owned 500-seat Performing Arts Center. Regular theatre organ concerts are given at the City Auditorium, home to a "Mighty Wurlitzer" restored by the local chapter of the American Theatre Organ Society. The Pinellas Park Arts Society holds monthly themed contests in the Park Station building, close to the Creative District. To encourage artists to live and work in the district, the city has established two facilities: Studios at 5663 and the Artist Live/Work building.

Automobile culture

[edit]The Tampa Bay Automobile Museum[19] displays an extensive collection of historical automobiles with an emphasis on progressive engineering achievement, the personal interest of founder and benefactor Alain Cerf. The museum houses a unique working full-scale replica of the first self-propelled mechanical vehicle, the fardier of Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot.[20] Luxury cars currently displayed and sold in Pinellas Park include Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, Bentley, McLaren, and Aston Martin. These and a Maserati dealership are all located in the Gateway area near the Automobile Museum.

Car and truck aficionados display their prized vehicles nearly weekly on 49th Street and compete in the regularly scheduled shows.[21] The Showtime Dragstrip provides a venue for drag racing fans.[22] Nearby on the aptly-named Automobile Boulevard is Tampa Bay Grand Prix, where youth and young adults race high-speed go carts on an indoor track.[23]

Community events

[edit]

Pinellas Park is known throughout the Tampa Bay area for a series of community events held annually in a city-owned bandshell located behind City hall. The most popular of these events is "Country in the Park", a festival held every year generally on the third Saturday of March, but always after the Florida State Fair and Florida Strawberry Festival. The festival's popularity stems from its wide array of events, such as arts and crafts shows, NASCAR displays, popular amusement park rides, and multi-artist day-long concerts, and the fact that parking, entry to the festival, and attendance of the concert are all free of charge. As of 2011, the Country in the Park festival has been organized for 21 years straight.[24] Another popular celebration among the locals is Pride in the Park. This celebration occurs during the week leading up to Country in the Park. Usually the night before Country in the Park, the firefighters' chili cookoff takes place at the bandshell.

Pinellas Park is home to a memorial to the Korean War, located in Freedom Lake Park.

Economy

[edit]Due to its proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and Tampa Bay, Pinellas Park is home to many marine businesses, from manufacturing to service and supplies. Large optical manufacturers, including Transitions Optical, are located either in Pinellas Park or nearby in the broader area known as "Gateway".[25]

In 2024 the city reported the unemployment rate of the 'immediate area' at 3.10%.[26] In 2020, the city reported total governmental-type and business-type assets of $271 million and total revenue from taxation and charges for services of $104 million.[27]

Lockheed Martin Aeronautics' Pinellas Park facility specializes in metal forming, fabrication and assembly of components for military and civilian aircraft. Current and prior projects include the F/A-22, F-16, C-130J, C-5, U2, Northrop's E-2C Hawkeye, the Gulfstream G5, Goodrich Aerospace, Piper, the P-3, Atlas Launch Vehicle, Space Shuttle, and B-52 Bomber.[28]

The C.W. Bill Young Armed Forces Reserve Center, a $47-million multi-facility training center for both U.S. Army Reserve and Florida Army National Guard units, opened in 2005 and serves thousands of soldiers yearly.[29]

Several of the largest employers in Pinellas County occupy parcels contiguous with the city, including Raymond James Financial, Transamerica Financial, Cisco, FIS (credit card services), Valpak (advertising mailers), Orbital ATK (defense electronics), and Home Shopping Network.

The city has three concentrations of retail business all along Park Boulevard. At 49th Street, near the historic center of town, one finds traditional shops, small businesses, and restaurants. Just to the east, at U.S. 19, the Shoppes at Park Place anchor the city's second retail hub with big-box retailers and a large movie theater. At the western edge of the city, near 66th Street and Belcher Road, are more big box retailers, ethnic specialty shops and restaurants, and the enormous Wagon Wheel and Mustang flea markets.

Due to the significant Vietnamese, Laotian, Indian, and southeast Asian community, Pinellas Park is home to one of the largest concentrations of ethnic restaurants, businesses, and specialty vendors serving those communities in the southeast. The city's library maintains the county's only special collection of materials in Vietnamese. The population includes those with recent ancestors from Germany, Poland, Eastern Europe, Russia, Armenia, India, Lebanon, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

The Pinellas Park Chamber of Commerce promotes the interests of local and nearby businesses, contributing to the overall vitality and cooperative nature of the mid-county economy.

Government

[edit]Pinellas Park has a council-manager form of government. The current mayor is Sandra Bradbury, who is the daughter of former mayor Cecil Bradbury.[30] The current city manager is Bart Diebold.[31] Various volunteer citizen boards are appointed by the city council to advise the council on governmental matters. The city council itself consists of four board members.

Police and Fire Departments

[edit]Pinellas Park's original police department was founded on May 27, 1915, with its only member being the appointed Marshal George W. Williams Sr. The modern Police Force was established in 1948.[7] Today, the city maintains a Police Department of more than 150 employees.[32] In 2023, Police Chief Adam Geissenberger assumed the role of police chief following the retirement on Police Chief Mike Haworth.[33] In 2015, Mike Haworth assumed the position previously held by Dorene Thomas, the first female police chief in the county.[34] The city announced in its 2020 budget that it will begin work on a $25 million construction project of a new Police and Fire Operations Center.[27]

The Fire Department was established in 1912, when the city had only 50 residents. It serves the city and the surrounding areas. In 2017, the city paid $915,000 for the site of a former church with the intention of building a new fire station. The city has announced construction of the new station will cost approximately $4.7 million. The Fire Department is led by Fire Chief Brett Schlatterer.[35]

Youth Programs

[edit]The Police Department facilitates the Police Cadets, a youth education and service group. Likewise, the Fire Department facilitates the Fire Explorers. Youth in both programs are involved in community service as well as competitions among similar groups.

Education

[edit]The city is served by the Pinellas County Schools district. Most of the city's high school students attend Pinellas Park High School[36] or Dixie M. Hollins High School.[37]

The Caruth Health Education Center is home to the healthcare-related degree programs of St. Petersburg College. It includes a simulation hospital unit for its nursing program, a patient-care clinic of dental hygiene, and an orthotics and prosthetics lab space.[38]

Library

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Madalya Fagan was the first president of the library association, and through the efforts of this volunteer organization, the Pinellas Park Public Library was established in December 1948. Fifteen years later, the city of Pinellas Park took control over the library. Marjorie Trimble was the very first paid librarian, although it wouldn't be until 1967 when Ms. Harrop would be the first librarian who possessed a Master of Library Science degree to be hired. The first library building was located in Park Station, an old pump house in the middle of Triangle Park. The second library was then built at 5795 Park Boulevard, although that structure no longer stands. The current library was built in 1969,[39] and is located at 7770 52nd St, across the street from City Hall and Pinellas Park Elementary School. The library was last remodeled in 2001 and has undergone several additions that expanded the original 7,000 square feet interior into 30,972 square feet, which includes over 26 adult desktop computers, 11 children desktop computers, a teen lounge, a quiet room, and two meeting rooms for rentals and programs.[40]

On June 6, 2014, the library was renamed in honor of late director Barbara S. Ponce. Mrs. Ponce was promoted to community activities administrator and library director in 1999, and retired in 2008.[41] The job placed her over the Pinellas Park Library, parks and recreation, and media/public events. [42]

Collection

[edit]The library houses a collection of over 100,000 physical items, including books, audio books, newspapers, magazines, DVD's, and Blu-ray discs available for holders of Pinellas Public Library Cooperative-issued library cards to check out. E-books and other digital services are also available.[43] Special collections include an Asian Language Collection with materials in Hindi, Mandarin, and Vietnamese, a Spanish Collection, and an extensive collection of graphic novels and Manga.

Programs

[edit]The Barbara S. Ponce Public Library hosts programs for community residents with many designed for children and teens.[44] [45] These programs include many art, music, and literature related educational programs as well as chess clubs, board game events, and programs to tutor schoolchildren with homework help.[46][47]

Adult programming consists of monthly craft nights, an adult coloring club, free movie screenings, murder mystery nights, and technology classes. English as a Second Language (E.S.O.L.), American Sign Language, Origami, and Ukulele classes are also hosted by members of the community in conjunction with the library.

Transportation

[edit]Pinellas Park is served by major roads such as U.S. Route 19, Florida State Road 693, Florida State Road 694, and is served by an exit off I-275.

Mass Transit through Pinellas Park is provided by Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority (PSTA).

While the Clearwater Subdivision railroad line runs through Pinellas Park, the city contains no stops on the line.

Nearby Tampa International Airport provides air transportation for most passengers.[48] Smaller airlines, with destinations to smaller cities and towns, operate at St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport, with most tenants providing only seasonal services.[49]

Notable people

[edit]- Nick Andries, racing driver

- Mike Cope, NASCAR driver

- Jesse Litsch, former MLB pitcher for the Toronto Blue Jays

- Browning Nagle, former NFL football player

- Stephen Nasse, racing driver

- Terri Schiavo, resident at a hospice during the case surrounding her end-of-life case

- Melissa Ann Shepard, Canadian-born criminal

- Roy Smith former MLB pitcher for the Cleveland Indians

- Rachel Wade, an American woman who was convicted of murder in the second degree in the murder of Sarah Ludemann

- Fez Whatley, radio personality

Gallery

[edit]-

U.S. soldiers with the Army Reserve Medical Command at the C.W. Bill Young Armed Forces Reserve Center

-

Inside view of Teen Lounge. Reserved for students in grades 6–12.

-

Young Adult books lining the shelves inside the Teen Lounge

-

Interior shot of Park Station

-

Clearwater Subdivision of CSX Transportation in Pinellas Park, 2016

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Pinellas Park city, Florida". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "2020 Census General Population Data".

- ^ Hartzell, Scott Taylor (2006). "Frank Allston Davis: He Lit Up the Town". Remembering St. Petersburg, Florida: Sunshine City Stories. The History Press. p. 54. ISBN 1-59629-120-6.

- ^ a b "Pinellas Park History". www.pinellas-park.com. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ "HISTORY OF PINELLAS PARK, FLORIDA". www.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ "History". www.pinellas-park.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015.

- ^ "Pinellas Park celebrates 100 years". Bay News 9. October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ Pinellas County Historical Background (PDF). The Pinellas County Planning Department. pp. 7–5.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Pinellas Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ "Pinellas Park Water Management District - Florida Stormwater Drainage". www.ppwmd.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Pinellas Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Pinellas Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Pinellas Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Pinellas Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ Chris Townsend. "Tampa Bay Automobile Museum". Tbauto.org. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Automobile Museum, in Tampa, Florida - Citroen 7 CV". Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Quaker Steak & Lube". July 13, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ "ShowTime Dragstrip Pinellas County Professional DragRacing". showtimedragstrip.us. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015.

- ^ http://tampabaygp.com Archived February 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Torres, Juliana A. (March 24, 2011). "Country in the Park attracts crowd". Pinellas Park Beacon. Pinellas Park, Florida. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ "Pinellas County Economic Development". Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "Pinellas County, FL Unemployment Rate Monthly Analysis: Metropolitan Area Employment and Unemployment | YCharts". ycharts.com. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report". www.pinellas-park.com. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ "Pinellas · Lockheed Martin". Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "Tampabay: Reserve training center debuts". www.sptimes.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2015.

- ^ "Mayor Sandra L. Bradbury". www.pinellas-park.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "City Manager". www.pinellas-park.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ Official web site retrieved November 15, 2012, "Welcome to City of Pinellas Park, Florida". Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ "Pinellas Park police chief announces retirement; new chief appointed". March 3, 2023.

- ^ "New Pinellas Park police chief leading into the future by building on the past". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015.

- ^ "Overview | Pinellas Park, FL".

- ^ "Pinellas Park High / Homepage". www.pcsb.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016.

- ^ "Dixie Hollins High / Homepage". www.pcsb.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016.

- ^ "About the Health Education Center". www.spcollege.edu. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "1968-1969 Construction of the New Pinellas Park Public Library | Pinellas Memory Digital Collection". pinellasmemory.org. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "History". Pinellas Park Public Library. Pinellas Park.

- ^ By. "Barbara S. Ponce Bids Farewell – Tampa Bay Library Consortium". Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Barbara Ponce, Pinellas Park Library Director and More, Remembered". June 28, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "Collection & Services". Pinellas Park Public Library. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Calendar". Barbara S. Ponce Public Library. Pinellas Park.

- ^ "Departments". Barbara S. Ponce Public Library. Pinellas Park. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ "Children's Programs". Barbara S. Ponce Public Library. Pinellas Park. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "Teen Programs". Barbara S. Ponce Public Library. Pinellas Park. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "Homepage | Tampa International Airport". www.tampaairport.com. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Home | St. Pete-Clearwater International Airport". www.fly2pie.com. Retrieved August 16, 2015.